News Post

FROM THE ALABAMA LAWYER: Am I the Last of My Kind?

Published on March 7, 2025

By Christy Crow

A few years ago, I was talking to a partner at a large Plaintiffs’ firm about a case we were working on together and he said, “Christy, I am proud of you. A lot of small-town attorneys have just given up and complain about the large firms, but not you. You’ve adapted.” My immediate reaction was to think that I didn’t know I had a choice -I have a family to support. Despite my cynical first reaction, his words stayed with me. The following weekend, my husband and I were riding dirt roads with some friends (yes, country lawyers still do that), and “Last of My Kind” by Jason Isbell came on and I thought, “Am I the last of my kind? Is the rural lawyer going the way of the dinosaur?”

In the Third Judicial Circuit where I live and have my primary office, there are four lawyers younger than me. They are all in their 40s.[i] Nationwide, there are 1.3 million lawyers, but they are mostly concentrated in cities, while many small towns and rural counties have few if any lawyers.[ii] Though about 20% of our nation’s population lives in rural America, only 2% of our nation’s small law practices are located there.[iii] A 2020 survey from the ABA found there were 1300 counties in the United States with less than one attorney per 1,000 residents, many with no attorneys at all.[iv]

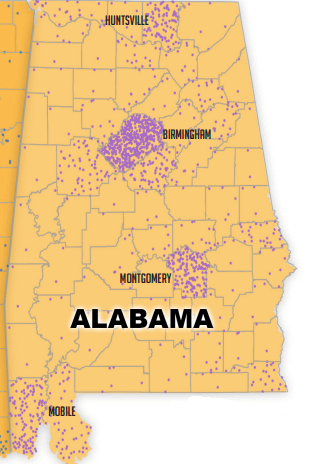

In Alabama, a third of our counties have 20 or fewer lawyers. Meanwhile, more than 68% of private practice lawyers are concentrated in just seven counties, even though these counties make up only 47.3% of the state’s population. Jefferson and Shelby Counties alone account for 40% of Alabama’s lawyers but just 17.8% of its residents.

The American Bar Association’s 2020 Profile of the Legal Profession highlights this imbalance, illustrating how Alabama’s lawyers are disproportionately concentrated in urban areas. This trend is not unique to Alabama—Georgia faces a similar divide, with 65% of its population living outside metro Atlanta, yet only 30% of the state’s lawyers practicing there.

A 2022 study by the Legal Services Corporation (LSC) revealed that approximately 92% of low-income Americans receive inadequate or no legal assistance for their civil legal problems.[v] This problem is especially acute in rural areas, where geographic isolation compounds existing barriers to accessing legal services. The LSC survey found there are 8,000,000 people in rural areas below 125% of the poverty level, and 77% of rural households had more than one legal problem in the past year.[vi] Residents in these regions often face long travel distances to the nearest attorney, if an attorney is even available.

The problem with the dearth of lawyers, especially younger lawyers, in rural areas is not limited to what happens to the parties in the Court systems. If there are no younger lawyers living and practicing in rural areas, there are no good lawyers to become good judges or lawyer legislators. This deficiency affects everyone, no matter where we practice or reside.

The Harvesting Hope Initiative

Alabama State Bar President Tom Perry, from Demopolis, recognized this problem prior to being elected Bar President. He created the Harvesting Hope Initiative in an effort to address the issue.[vii] Once studied, the problem showed itself to be more acute than thought: actually, a dearth of lawyers exists in both rural areas and urban areas, or at least in portions of many urban counties. While the pending crisis is more pronounced in the State’s rural areas, with changing demographics, the paucity of lawyers will become an issue in most, if not all, urban counties as well.

Identifying Opportunity Zones for lawyers across the State, President Perry, with the help of Tom Heflin from Sheffield, began examining other States’ practices to determine how Alabama can help lawyers address the crisis and tap potential opportunities. President Perry and Heflin have identified a handful of target counties and developed an economic model to exhibit the financial viability of practicing law in rural counties. The financial model also reveals the potential for a reasonable and sustainable income for the participating lawyer. President Perry and Heflin have spoken with judges and lawyers to identify potential mentors, future employers, and shared office space or incubator programs where interested young lawyers may be placed. One of the goals of the Initiative is to empower rural leaders and professionals with the knowledge of the positive economic impact recruiting young lawyers and other professionals can have on a community and to encourage participation from these economic development leaders, as well as other lawyers. The goal is to expand Harvesting Hope from the initially identified counties to all circuits and counties facing this crisis.

Similar Efforts Across the Nation

The National Center for State Courts has also created the Rural Justice Collaborative, a partnership between the National Center for State Courts and Rulo Strategies.[viii] The Rural Justice Collaborative selected 25 of the country’s most innovative rural justice programs to serve as models for other communities. These programs include a rural incubator project for lawyers in North Dakota, a youth court in Mississippi, and a reaching rural initiative in South Carolina.

The Ohio Rural Practice Incentive Program is a state-funded initiative administered by the Ohio Department of Higher Education. “Lawyers who commit to a minimum of three years and up to five years in an underserved community can receive up to $10,000 per year toward student loan repayment.”[ix]

South Dakota recognized the problem over a decade ago, identifying a town of about 1,000 people that had a single 85-year-old practicing lawyer.[x] In response, the South Dakota Bar Association formed a task force that ultimately led to the development of a 2013 law in South Dakota creating a pilot program with an annual subsidy of $12,000 for 5 years for lawyers practicing in rural areas.[xi] The program has placed attorneys in 26 counties and offers financial incentives to attorneys who practice in designated areas for at least five years.

North Dakota, suffering from similar shortages, created a $45,000 state subsidy to attorneys working in rural areas which will be paid in five equal, annual payments. The Supreme Court of North Dakota will pay 50% of the incentive, the city or county will pay 35%, and the North Dakota Bar Association will pay 15%.[xii]

California has similar issues with getting lawyers out of the population centers. In response, UC Davis School of Law developed a Law and Rural Livelihoods seminar.[xiii] UC Davis Law Professor Lisa Pruitt has been bringing attention to these issues for years. “I teach a course called Law and Rural Livelihood, which exposes students to what makes rural communities different, what some of the legal issues are, and how they play out in rural communities.”[xiv] In doing so, Professor Pruitt believes that this is another step toward alleviating the rural lawyer shortage.

Likewise, Maine is trying to reach potential student participants while they are still in law school. Its legislature proposed funding a three-year pilot program where students at the University of Maine School of Law spend the first half of their education on the school’s campus in Portland and then transfer to Fort Kent, where these students can work under the supervision of a professor in a satellite office of the college’s student legal aid clinic. Students receive academic credit for their work and reside in dorms of another state college campus in town. Clients would primarily be people with low incomes who cannot afford to hire an attorney of their own.[xv]

In Nebraska, where 12 of 93 counties have no attorneys and most counties have fewer than 20, state schools began attracting candidates for rural practice before law school. In 2016, three state schools — Chadron State College, the University of Nebraska at Kearney, and Wayne State College — began recruiting rural incoming college freshmen to pursue legal careers outside Nebraska’s urban areas, realizing that rural students were more likely to return to these rural areas to practice law. The students receive free undergraduate tuition and guaranteed admission to the University of Nebraska College of Law in Lincoln if a minimum 3.5 GPA is maintained and admissions standards are met.[xvi]

Alabama’s Finch Initiative

In Alabama, the University of Alabama Law School and Covington County Circuit Judge Ben Bowden developed the Finch Initiative in 2017. The fellowship is designed to provide an opportunity to experience the life of a small-town lawyer. It has grown from one Circuit in 2017 to four fellowships in 2024, including one in my circuit. The University of Alabama School of Law hopes to continue growing the program to reach other rural areas of Alabama.[xvii] Equal Justice Works, a nonprofit organization that promotes law and public service, has a similar program that allows law students to participate in the Rural Summer Legal Corps and addresses the access to justice crisis for people living in rural areas.[xviii]

Getting younger lawyers into rural areas is not the only solution, although arguably it could be the best. The Justice4AL Program started by Immediate Alabama State Bar Past President Brannon Buck provides access to legal resources across the State.[xix] Providing self-represented litigants access to standard forms and how-to videos for self-representation brings access and convenience to the public.[xx] Remote video access to courts allows lawyers and judges access to the Courts with little to no travel time. It can be argued that it is not the number or location of lawyers creating this issue of unmet needs, as much as it is the costs associated with hiring an attorney, at least in the civil arena.[xxi] To address this concern in criminal representation, Alabama has allowed limited scope representation or unbundling of services.[xxii]

Why Practice in Rural Alabama?

First… there’s the dirt roads. Living and working in rural Alabama (or rural America) is simpler in many ways. While I may drive farther for fine dining, I can sit on my porch and have a clear view of the stars and was even able to see the Northern Lights this summer from my front porch. The night sounds of the symphony played by crickets, tree frogs, and cicadas are tranquil and fulfilling following a day of satisfying legal work.

Others have recognized that the practical benefits of small-town lawyering include a lower cost of living, minimal commutes, and a slower pace of living.[xxiii] While some wonder whether it is financially viable to practice law in rural areas, the numbers presented by President Perry and Heflin show that it is possible. The law of averages works on the side of rural practice as well. An average of 843,686 cases are filed in Alabama annually, with 39% of those being filed in the seven counties where 68% of the lawyers practice. That means, on average, there are 134 cases per available attorney in the rural counties versus 39 cases per available attorney in the seven identified urban counties.

Also, most rural lawyers know a little bit about a lot of different areas of law. A rural practice may touch personal injury, product liability, estate planning, tax law, criminal law, family law, and bankruptcy. As a result, rural attorneys can often identify potential new theories or see opportunities that others might miss. The opportunity to be involved in cases outside of one’s normal fields, and to refer cases to others, fosters establishing relationships with lawyers around the State or country. In turn, those attorneys may call you when they have a need you may be uniquely qualified to meet.

Finally, the benefit of living and practicing in a rural area is this: I live in a community with those around me. One of my favorite clients brought me butternut squash from his garden and is planting parsnips for me this winter. He also called me when his Medtronic diabetes pump was recalled, starting me on a journey to one of the biggest cases of my career. I got to know another long-time client when I coached her daughter in basketball 20 years ago. A few years ago, I was able to host that same daughter’s baby shower at my house, after having represented her cousins and friends in various personal injury cases throughout my career.

Leo Rosten is quoted as saying, “The purpose of life is not to be happy, but to matter – to be productive, to be useful, to have it make some difference that you have lived at all.” The rewards associated with living and working in the rural community where I practice will far exceed any missed urban legal opportunities or perceived prestige. Most importantly, if you decide to join me in rural Alabama, you will remember that you matter every day.

[i] We do have several lawyers that practice here but commute from more urban areas. [ii] https://www.americanbar.org/news/profile-legal-profession/demographics/?utm_source=chatgpt.com Legal deserts threaten justice for all in rural America, https://www.americanbar.org/news/abanews/aba-news-archives/2020/08/legal-deserts-threaten-justice [iii] Lisa R. Pruitt, et al. Legal Deserts: A Multi-State Perspective on Rural Access to Justice, 13 Harv. Law & Policy Review 16 (2018). [iv] https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/news/2020/07/potlp2020.pdf [v]Legal Servs. Corp., The Justice Gap: Measuring The Unmet Civil Legal Needs Of Low-Income Americans 13 (2022) https://justicegap.lsc.gov/ [vi] Id. [vii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pLiDCMgEZSw [viii] https://www.ruraljusticecollaborative.org/ [ix] https://perma.cc/LSP6-CRBR [x] Kristi Eaton, Rural areas struggle with lack of lawyers, https://www.mprnews.org/story/2011/12/12/rural-lawyers, 12/12/2011. [xi] Ethan Bronner, No Lawyer for Miles, So One Rural States Offers Pay, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/09/us/subsidy-seen-as-a-way-to-fill-a-need-for-rural-lawyers.html#:~:text=The%20new%20law%2C%20which%20will,of%20South%20Dakota%20Law%20School, 4/8/2013. [xii] https://www.ndcourts.gov/rural-attorney-recruitment-program [xiii] https://law.ucdavis.edu/course/law-and-rural-livelihoods [xiv] https://www.ucdavis.edu/blog/curiosity/how-do-we-resolve-rural-lawyer-shortage [xv] https://www.marketplace.org/2022/03/28/in-maine-hopes-turn-to-law-students-amid-dearth-of-rural-attorneys/ [xvi] April Simpson, Wanted: Lawyers for Rural America, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2019/06/26/wanted-lawyers-for-rural-america 6/26/2019. [xvii] Those interested in developing a Finch Fellow for their circuit can contact Caroline Strawbridge at the University of Alabama School of Law. cstrawbridge@law.ua.edu. [xviii] https://www.equaljusticeworks.org/law-students/part-time-summer/rural-summer-legal-corps/ [xix] https://www.justice4al.com/ [xx] While self-represented litigants might solve some of the problems with lawyer shortages, a 2018 survey of judges found that 62.5% of judges found self-represented litigants to be a significant stressor for judges. David Swenson, Ph.D., L.P., et al., Stress and Resiliency in the U.S. Judiciary, 2020 Journal of the Professional Lawyer, 1. [xxi] Mark C. Palmer, The Disappearing Rural Lawyer, Part II, Future Law, 1/16/20 https://www.2civility.org/the-disappearing-rural-lawyer-part-ii/ [xxii] For more information about limited scope representation, visit https://www.alabamaatj.org/i-can-help/limited-scope-representation/. [xxiii] Roy S. Ginsburg, Be a Small-Town Lawyer, https://www.attorneyatwork.com/be-a-small-town-lawyer/ 6/12/22.