News Post

FROM THE ALABAMA LAWYER - Patent Issues for the Non-Patent Lawyer

Published on April 16, 2024

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Joe Bird

This article is an introduction to patent issues for the lawyer who is not a patent attorney. It is meant to provide the non-patent lawyer the ability to identify issues and provide initial guidance for a client who might have a patentable invention, or who might receive a notice of patent infringement.

A patent is a right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling an invention throughout the United States or importing it into the United States.[1] If the invention is a process, the patent may exclude others from using, offering for sale, or selling throughout the United States, or importing into the United States, products made by that process.[2] A recipient of a patent is called a patentee. A common misconception is that a patent enables the patentee the freedom to do or sell something covered by the patent, but that is not true. A patent only allows the patentee to stop others from doing or selling something. Freedom to operate is a separate question from whether a patentee can get its own patent.

There are different types of patents. A utility patent (as opposed to a design patent, discussed below) may be issued by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) for the structure, function, or composition of a physical object or for a process. The statutory list of patentable subject matter is “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof.”[3] Patentable physical objects include a machine, a component, or a compound such as a pharmaceutical or a fertilizer. A patentable process can be for software or for manufacturing a physical product, among other things.

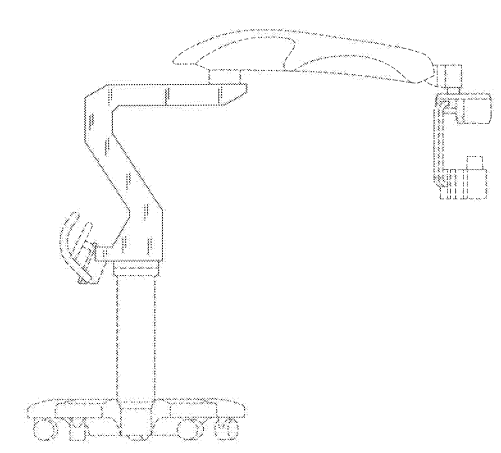

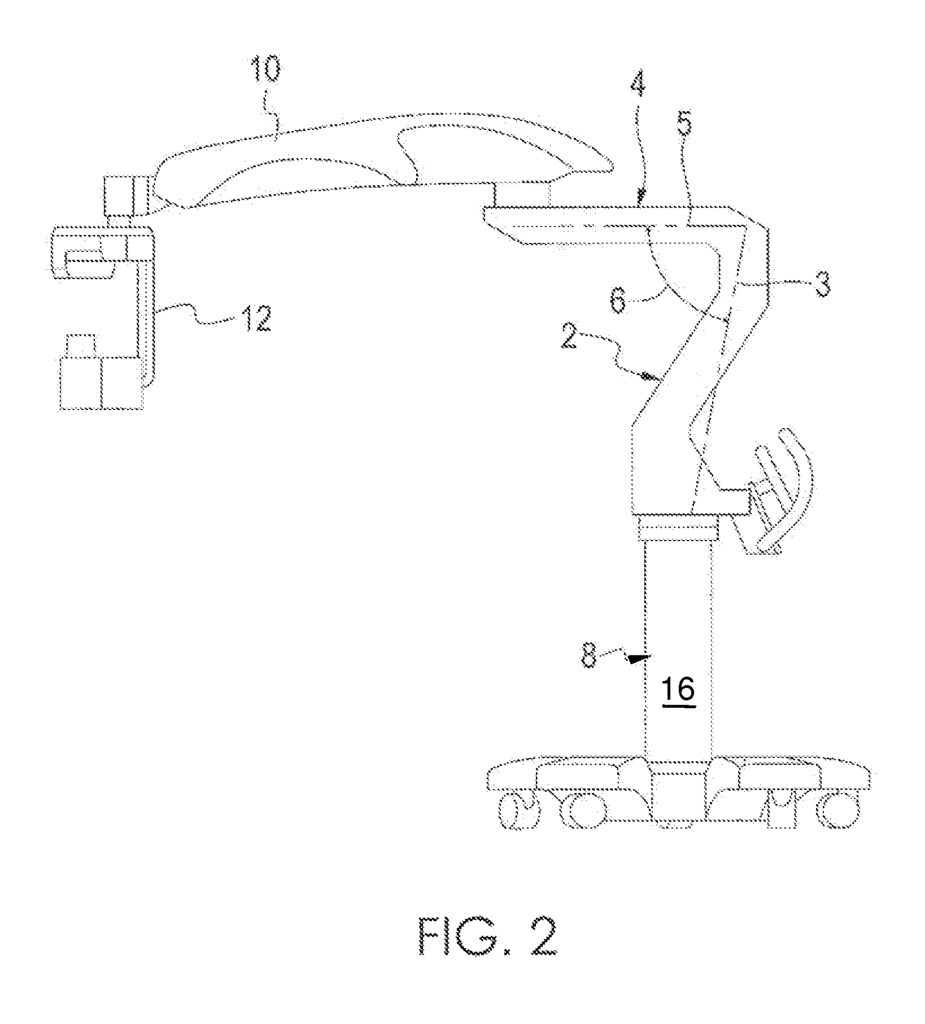

A design patent is different from a utility patent in that it protects the appearance of an object rather than its function, structure, or composition. For example, a stand for a surgical microscope could have a utility patent that covers its structure and can also be covered by a design patent that covers its appearance. For example, U.S. patent number 8,584,994 (utility) and U.S. patent number D685,405 (design) protect the structure and the appearance, respectively, of the same object. Design patents require only the filing of high-quality drawings of the object and a cursory description of those drawings.

Another common misconception about patents is that patent applications are simply rubber stamped by the federal government. The filing of a patent application by no means requires issuance of a patent. Patent applications are substantively reviewed by the USPTO to determine whether the disclosed invention is patentable. A patentable invention must be both novel and non-obvious. In lay terms, novelty means there is nothing else exactly like it that has been publicly displayed or previously produced by a third party or the inventor herself. U.S. patent law defines novelty as not having been “patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention.”[4]

Non-obviousness is a more difficult concept than novelty, however, and non-obviousness is the battlefield upon which most patent prosecutions are fought. Obviousness is a bar to a patent “if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious before the effective filing date of the claimed invention to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains.”[5] Prior art includes patents, patent applications, and non-patent literature (articles, advertisements, product manuals, and the like) by others that were made public before the priority date of the applicant’s own application. This standard is difficult to apply (and the subject of much litigation) and perhaps may be best explained by an example: imagine a first piece of furniture with wheels on the legs, say a chair. After it becomes public, this piece of furniture would make a later-filed patent application covering a table with wheels on the legs obvious, and the application would be rejected by the USPTO on that basis. Obviousness normally is supported by a patent examiner’s combination of two or more prior art documents having all the features and functions of the invention applied for that, in the patent examiner’s opinion, would have been obvious to combine by a person of at least ordinary skill in the art. Or at least that is what the patent examiner says and this is where the battle in prosecution often occurs.

Because the content of prior art can be so important to the success of a patent application, an inventor should investigate whether any similar invention exists before filing a patent application and may purchase a patentability search report from one of a number of vendors for this purpose. The search report is not a guarantee of patentability, but it can identify other similar products, processes, and the like. The cost for a patentability search report typically does not exceed $1,000 under normal circumstances.

If the client has interest in possibly protecting an invention with a patent, another critical consideration is whether the client herself has used the invention publicly already. In the United States, an inventor must apply for a patent within one year from any public use of, disclosure of, sale of, or offer to sell the invention. If the inventor wants to apply for a patent in any foreign country, however, in most countries there is no grace period at all, and any public use, disclosure, sale, or offer to sell prior to the filing of a patent application would prevent issuance of a foreign patent. Use of the invention only for beta-testing by a potential customer does not necessarily constitute public use or offer to sell, but it is a risky practice to engage in before filing a patent application. If a client approaches a patent attorney with an invention for which there has been very limited disclosure to third parties, one avenue is to treat the prior disclosure as a beta-test if the facts support it. For a beta use, there should be a written agreement stating expressly that the use is beta only and specifying that the potential customer must provide feedback to the inventor for R&D purposes, and that the potential customer will not disclose the invention in any way. Beta use is not the safest course and, if it is pursued, it needs to be defined in a clearly written document signed both by the client and the potential customer. For these reasons, one of the first questions to be asked of an inventor is whether any public use, disclosure, sale, or offer to sell has been made; if so, a clock may already be running on the deadline to file for patent protection.

If your client wants to pursue a patent application, you should refer the client to a patent attorney or a patent agent. Only persons admitted to the patent bar can represent an inventor in a patent prosecution before an examiner in the USPTO. A patent agent is not a lawyer but has passed the patent bar examination and can also prosecute patent applications for others.

The background and process of filing a patent application works this way. Utility patent applications require a good bit of time and preparation. Prior to filing a utility patent application, a common first step is the filing of a provisional application. The sole function of a provisional is to acquire a priority date, and the provisional is not examined by a patent examiner – examination occurs only for a utility or a design patent application. The priority date means that, after the provisional is filed, another person who files a patent application on the same invention or makes public use of the same invention will not have patent rights superior to those of your client or be able to bar your client’s application. If the provisional application does disclose the entire invention, then a provisional can be converted to an application for a utility patent, also called a nonprovisional patent application, claiming priority to the provisional. This can be done within one year of the provisional’s filing. In this way, the provisional can provide an earlier priority date for the nonprovisional, but only for what is disclosed in the provisional. A provisional application is often advisable because it gives the inventor time to decide if investing further in the product and a nonprovisional patent application is worthwhile. Once a provisional has been filed, then later public use, disclosure, sale, and offers to sell (either by the inventor or by third parties) do not bar later patentability, either domestic or foreign. A provisional application is informal and can include hand drawings, provided that it must disclose all of the patentable features of the invention. Small- to medium-sized businesses can benefit greatly from filing a provisional: the low cost buys an early priority date and the succeeding year can be used to decide whether to spend money on a nonprovisional. If the client elects not to convert the provisional within a year, then it is abandoned and remains unpublished, and the client’s information remains confidential.

The cost of pursuing a patent can vary greatly. Many patent attorneys will not charge for an initial discussion to understand what the invention is and whether there are any issues (like prior use or public disclosure) that may have already impacted patentability. After a decision to pursue a patent has been made and an attorney client relationship has been established with an engagement letter, the next decision is whether to file a utility application (and then whether to file a provisional or a nonprovisional application), a design patent application, or both.

If an inventor decides to pursue a provisional application, she should prepare a written description of the invention and handwritten drawings and, if only minimal editing and additions are required by the patent attorney, the total cost for filing can be as low as a couple of thousand dollars. A nonprovisional, also called a utility application, is normally much more time-consuming and can be elected as the first step if the client wants to obtain a patent more quickly. The nonprovisional requires a lot of additional work over what is required for the provisional, including formalities such as detailed professional drawings, and the patent attorney must prepare patent claims. Patent claims in an issued patent are like a real property description in a deed – the patent claims define the metes and bounds of the invention and must adhere to very strict rules. An inventor can file her own patent, and some do, but one would be concerned about the validity and accuracy of the patent claims if enforcement were ever needed. The cost of a nonprovisional depends greatly on how much work the inventor does to define the invention and represent it in drawings. The less information and explanation the inventor provides to the patent attorney, the more attorney fees are incurred. The amount of work by the inventor has more influence over the cost than does the complexity of the invention. For a design patent, the cost of preparing the application is more in line with the cost of a provisional application, assuming the inventor can prepare detailed drawings.

The amount of time between filing a utility/nonprovisional and issuance of a patent, if one ultimately issues from the application, varies greatly. An applicant can pay an extra fee for expedited review, which can result in a decision on patentability within one year. Without paying for expedited review, the process normally takes two to four years. Design applications are typically processed more quickly, normally being examined within a year.

The policy behind the granting of patents is that inventors receive a monopoly (20 years for a utility and 15 years for a design patent) from the date of filing of the application, and the public in return receives a written disclosure of the invention (in the form of a published and publicly available patent). Because patents are disclosed publicly and have a limited term, sometimes it is better not to pursue patent protection for a manufacturing method or recipe that can be protected as a trade secret for much longer than the term of a patent. But, if the method or recipe for producing a product can be “reverse engineered” by another person, then a trade secret strategy may prove to be inadequate.

The point in the inventive process that the inventor has reached is also important in determining whether to pursue patent protection. To be patented, inventions must be conceived of and reduced to practice. Conception occurs when one or more people (there can be and often are multiple inventors for a patent) have conceived of the invention in all aspects. Reduction to practice can be actual (e.g., a prototype) or constructive (e.g., describing all aspects of the invention on paper). The filing of a patent application does serve as constructive reduction to practice of the subject matter described in the application if enough detail is provided.

Conception and reduction to practice bring up the need for clarity as to who owns the rights to an invention. Under U.S. law, patent rights belong initially to one or more inventors, all of whom must be a person (not a company or other entity). Patent rights, on the other hand, can be assigned in writing to other persons or entities. If no such assignment is made, patent rights remain with the individual inventors. It is sometimes debatable whether a person is a co-inventor or has only helped in reduction to practice. An employer or principal should require any employee or contractor (working in any way on a project that could lead to an invention) to sign an agreement including an NDA, a written assignment, and an inventor’s oath form which can be filed in the USPTO with the patent application. NDAs should also be signed by any third party from whom the client is seeking work or advice of any kind before a confidential disclosure of the invention is made, an exception being that potential investors normally do not sign NDAs.

A major consideration for whether to invest in getting a patent is whether the client has the skill and resources to commercialize the invention. Patents, by themselves, are not normally sold. A company or individual who is already in the business related to the invention is most suited for patent protection. That is, if the invention is a one-off idea, even brilliant, thought of by someone not already in the business related to the invention, the inventor can find it hard to realize any benefit from a patent unless he starts a business selling or using the invention. If the client can establish good sales and possesses a patent on the invention, then sale of the invention and the business relating to the invention to another is more plausible. Patents are also not self-enforcing, so another consideration on whether to invest in a patent is that patent infringement litigation can be very expensive. Full cost for infringement litigation would normally be at least six figures and more likely seven figures, although some patent litigation firms will take a case on a contingency basis against an infringer with deep pockets.

A company seeking to raise equity from investors should consider patenting important inventions because potential investors often take patent protection into consideration. This is not because a patent is guaranteed to stop a competitor from infringing, but because the threat of patent litigation can at least slow a competitor’s plan to infringe. In that way, a relatively small investment in good patents can be worth more to a small company than to a larger one.

Claims of patent infringement against your client are another matter. Your client might receive a cease-and-desist letter alleging patent infringement. If that letter does not contain certain information – and even if it does but later turns out to be frivolous – it could be deemed to be an assertion of patent infringement made in bad faith prohibited by Alabama Code § 8-12A-2. Damages can be awarded for mere receipt of a frivolous demand letter, and this code section should be considered for inclusion in a response to a patentee who has sent a frivolous demand letter. Cease-and-desist letters for patent infringement were more rampant until recent changes in the law, which now require that a patent infringement case must be filed where the defendant does business, but they can still be of concern. A registered patent lawyer, or a patent litigator, should be consulted upon receipt of such a letter.

Patents can represent opportunities for business clients in certain circumstances, especially when the invention is connected to the client’s existing business. But before filing a patent application, the client should have a good understanding of the required investment of costs and resources required for patent prosecution. One efficient way to explain this would be to have your client read this article and then discuss with you whether to take the next step of investigating the patent process with a patent attorney.

Figure 3 of U.S. Patent No. D685,405 (design patent):

Figure 2 from U.S. Patent No. 8,584,994 (utility patent):

Endnotes

[1] 35 U.S.C. § 271(a).

[2] 35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(1).

[3] 35 U.S.C. § 101.

[4] 35 U.S.C. § 102.

[5] 35 U.S.C. § 103.